Princely Tongues: The Languages of Europe’s Five Smallest Countries

Tiny countries are fascinating. They always remind me of fairy tales (“there was a small kingdom where everybody was happy”), even if with some un-Grimm-ly tones (“they happily never paid a dime of taxes ever after”). They also tell us something about the history of Europe and its languages.

For this journey, I chose European countries with less than 100,000 inhabitants, excluding small countries like Malta, with almost half a million inhabitants, and Luxembourg, a giant compared to these very compact states.

I must confess a very personal reason to write about these countries. It was in Andorra that I peered into Europe’s linguistic marvels for the first time. Going there as a child in one summer holidays, I listened to a very strange language that was neither French nor Spanish. No one told me about it at school. I was hooked for life.

Andorra: two princes, one language (or rather four)

Andorra is the largest of these very small countries and the only one with more than 50,000 inhabitants. It is a principality, and a very special one: it is a diarchy, since there are two princes. One is called Joan Enric Vives i Sicilia, the bishop of Urgell, in Catalonia. The other is called Emmanuel Macron and is president of France in his spare time.

This peculiar situation is the consequence of a very ancient arrangement between the bishop of Urgell and the Count of Foix. They decided — for very medieval reasons — to share the valleys of Andorra as an indivisible unit. The bishops kept the right to be called prince of Andorra up to the present time, while the other princely title was transferred a number of times until it ended up at the desk of the French President — who thus is, by law, a prince (or, more precisely, a co-prince).

The story of this principality includes a Napoleon invasion and a 20th-century usurper who was neither Spanish nor French — his name was Boris Skossyreff, from Russia. I kid you not: there was a Russian King of Andorra. The Spanish Guardia Civil entered the principality at the request of the bishop (who very much enjoyed being prince) and expelled the Russian. Boris ended up in Algarve, as people do.

What is the language of Andorra? The principality is in the middle of Catalan Pyrenees, between Catalonia and the South of France. People in villages on the Spanish side didn’t speak Spanish till the 20th century. The French side includes a part of North Catalonia (ceded to France in the 17th century) and regions who traditionally spoke Occitan.

When Andorra finally invested itself with all the trappings of a modern State — a constitution, UN membership, full democracy — it recognized on paper what had been a reality for centuries: Catalan was the language of Andorrans. It is the sole official language of the principality.

Many of the present-day countries in Western Europe (Spain, France, Germany, Italy) are the result of unification processes, some of them quite recent. These political processes were generally accompanied by the temptation to impose one single language, with one single standard, throughout the whole territory of a country. This gave rise to a very simplistic vision of languages in Europe: in France, the language if French; in Spain, the language is Spanish; in Italy, the language is Italian — and so on.

Andorra was a political oddity that allowed people who noticed it to see what was below such crude convergence of national borders and languages. Today, fortunately, almost everyone recognizes languages like Catalan or Basque and it is not such a surprise to learn that Andorra gave neither French nor Spanish any official status.

The language in which all official documents in Andorra are written is Catalan. The language on the road signs is Catalan. The name of the capital is Andorra la Vella, not Andorra la Vieja… On the street, besides Catalan, you hear a lot of Spanish, some French and some Portuguese.

Monaco: one prince, two languages

Let’s cross the border into France. After a drive through Côte d’Azur, we find another tiny country: Monaco.

It is a curious place, which seems to have been invented just so that French society magazines would have a royal family to entertain themselves. That may be not the real explanation — but Monaco is nonetheless an anomaly in the tidying up of European borders over the last centuries.

What is the official language of Monaco? It is, without much doubt, French. However, there is also a language called Monegasque, which is spoken increasingly less, but is taught in schools and heard from the mouths of some older inhabitants. We can see it in some street signs, as an example of the very European tendency to wait for minority languages to be almost extinct before showing them on the street.

The Monegasque version of the Monaco anthem starts with these two verses: “Despœi tugiù sciü d’u nostru paise / Se ride au ventu, u meme pavayùn”.

These words give us a hint that Monegasque is closer to the system of languages and dialects of Italy than to that of France. It is, in fact, considered by linguists a variety of the Ligurian language, spoken around Genoa (also increasingly replaced by standard Italian).

Liechtenstein: one prince and two German languages

If we go deep into the Alps, we reach a country which is, let’s face it, impossibly difficult to spell without checking.

Just like Andorra and Monaco, Liechtenstein is a principality. These are not countries we normally associate with humility, but they all seem to avoid using kingdom in their names. Perhaps a limited territory entails a certain sense of proportion in this regard (Russian kings of Andorra notwithstanding).

Liechtenstein is one of the few monarchies in the world where the monarch still has actual powers — in return, the population has the right to remove the prince from the throne. In practice, nothing really happens. It’s a far too small and a far too rich country to have serious constitutional crises.

Officially, this is a German-speaking country, a remnant of the incredibly complex collection of small states called the Holy Roman Empire. On the street, we will hear something very similar to Swiss German, a collection of Alemannic dialects quite distinct from Standard German. Liechtensteiners will speak in Alemannic and write in Standard German, a typical example of diglossia. If they go to a Swiss university, they will talk in formal Standard German during classes; during breaks, they will talk in Swiss German with Swiss friends and (informal) Standard German with German friends.

San Marino: two captains, two languages

Let’s cross the Alps and enter Italy from the North. We pass by Milan and Bologna and let ourselves be carried along the freeway to the Adriatic coast. There, in the Rimini area, we look for “San Marino” in road signs.

When we finally get there, we enter what many claim to be the oldest republic in the world, with origins in the 4th century A.D. According to the country’s official history, the republic became independent from the Roman Empire! Today, it is the last trace of the patchwork of small countries that was Italy until well into the 19th century. Like Andorra, San Marino is a diarchy. The head of State is composed of two captain regents, chosen every six months.

Understandably, San Marino has Italian as its official language. On the street, you can still hear Romagnol, which is in danger of disappearing, as are so many languages and dialects all over Europe, swept away by the strength of standard languages used at school.

Vatican City: two languages (and two popes)

From San Marino, we can go back into Italy by foot. We get back into the car and follow the road to Rome, the only city that can boast a sovereign neighbourhood: Vatican, the smallest independent territory in the world. There are no two princes around, Andorra-style, but rather two popes — although only one of them is the sovereign.

The Vatican is a territory under the sovereignty of the Holy See, the Catholic diocese of Rome, an entity that maintains diplomatic relations with many nations across the world. For this reason, many countries have two embassies in Rome: one embassy to Italy and one to the Holy See. No embassies are located within the Vatican itself because, well, there is no space.

The Vatican belongs to the Holy See, but they are legally separate — the Holy See claims an existence of around 2000 years; Vatican City was created in 1929 by a treaty between Italy and the Holy See. This legal distinction has a very curious linguistic representation: the official language of the Vatican is Italian, but the official language of the Holy See is Latin.

The Latin language used by the Holy See is not exactly the Latin of Cicero. It is the Ecclesiastic Latin developed by the Catholic Church over the last 2000 years, which has many specificities, starting with the pronunciation, much closer to Italian than classical Latin would be. The Latin word «villa» would be read, in Roman times, a bit like «weela», but is read by Church Latin speakers as «veela». There’s more: a discourse in Latin by a member of the Curia may well include words like “microphonum”, which would baffle any ancient Roman.

The tiny country that wasn’t

It happened in the five countries we visited above: the processes of national construction left a few stray territories behind, which ended up as states in their own right, albeit minuscule in size and hardly conforming to the modern concept of a nation. We could say they are the counterpoint to nations without states: these are states without nations (but, let’s be honest: the concept of nation is difficult to pin down).

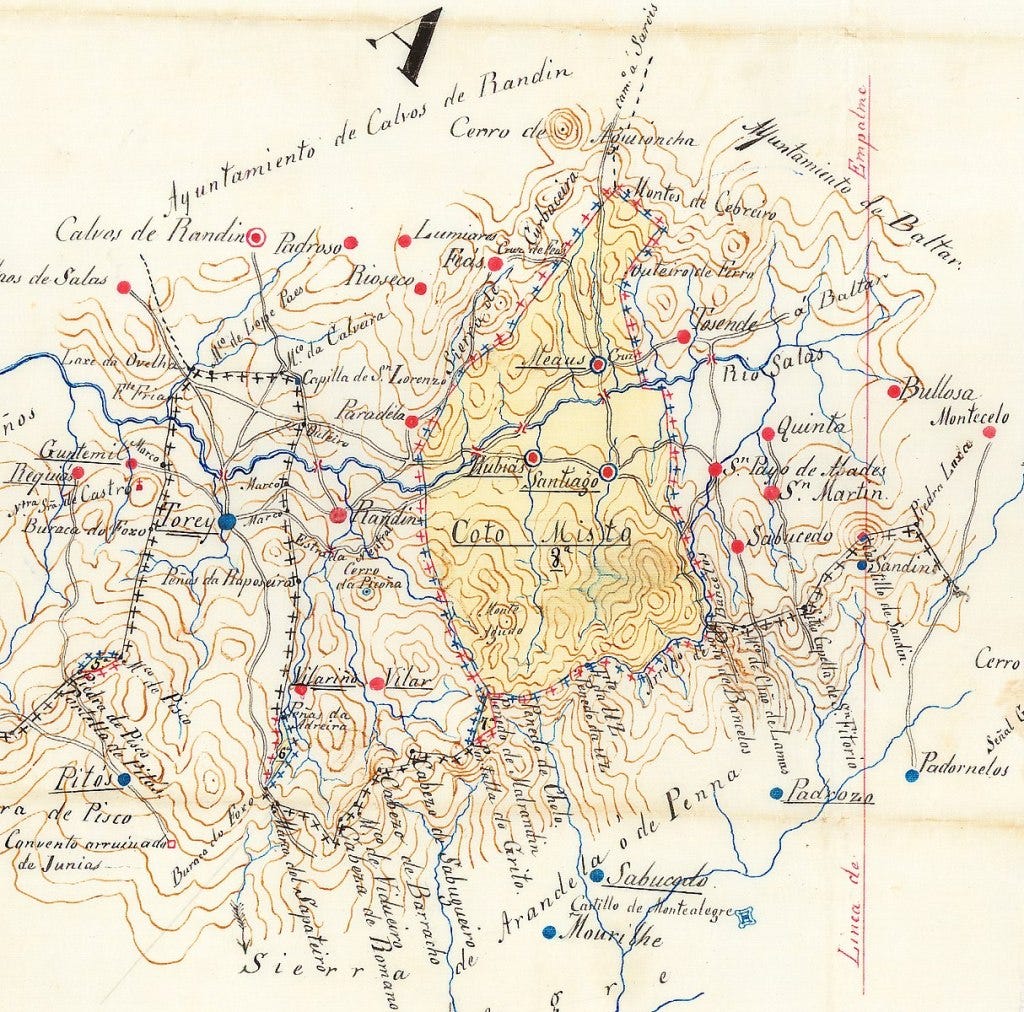

It could have happened in other places. In my own country, in its northern border, there was a small territory controlled by neither Portugal or Spain that could easily have been the basis for another one of these tiny countries. I’m talking about Couto Misto, which existed for centuries before its official partition in the 19th century.

What language was spoken there? In those small villages you wouldn’t speak Spanish, certainly, except in very particular situations. Nor would standard Portuguese be heard so far away from big cities… What was spoken was a language that would be called Portuguese on one side and Galician on the other. These two names, in the 19th century, around the Northern border, would still point to identical ways of talking. We would be hard pressed to know which speakers were Galicians and which were Portuguese — in fact, we can still find older people living by the border whose speech is very difficult to pin down to Galician or Portuguese. In Couto Misto, where no one was Portuguese or Spanish, the name of the language would be what mattered least.

It was only during the 20th century that the border between Portugal and Galicia — one of the oldest borders in the world — began to clearly mark, in the language heard on the street, a clear division between a Portuguese language increasingly invaded by the typical forms of the South and a Galician sharing more and more mental space with Castilian Spanish.

When we look at normal, non-tiny, European countries we tend to focus on the history of how a specific variety ended up as a national standard. That’s what happens when we talk about the history of French, the history of Spanish, the history of German, the history of Italian — or any other of the national languages of European nation-states.

Looking at the languages of these tiny countries, much less invested in grand national narratives, allow us to glimpse the diversity of languages that exists below the neat and misleading mosaic of European national languages.